A Garden To Banish Loneliness

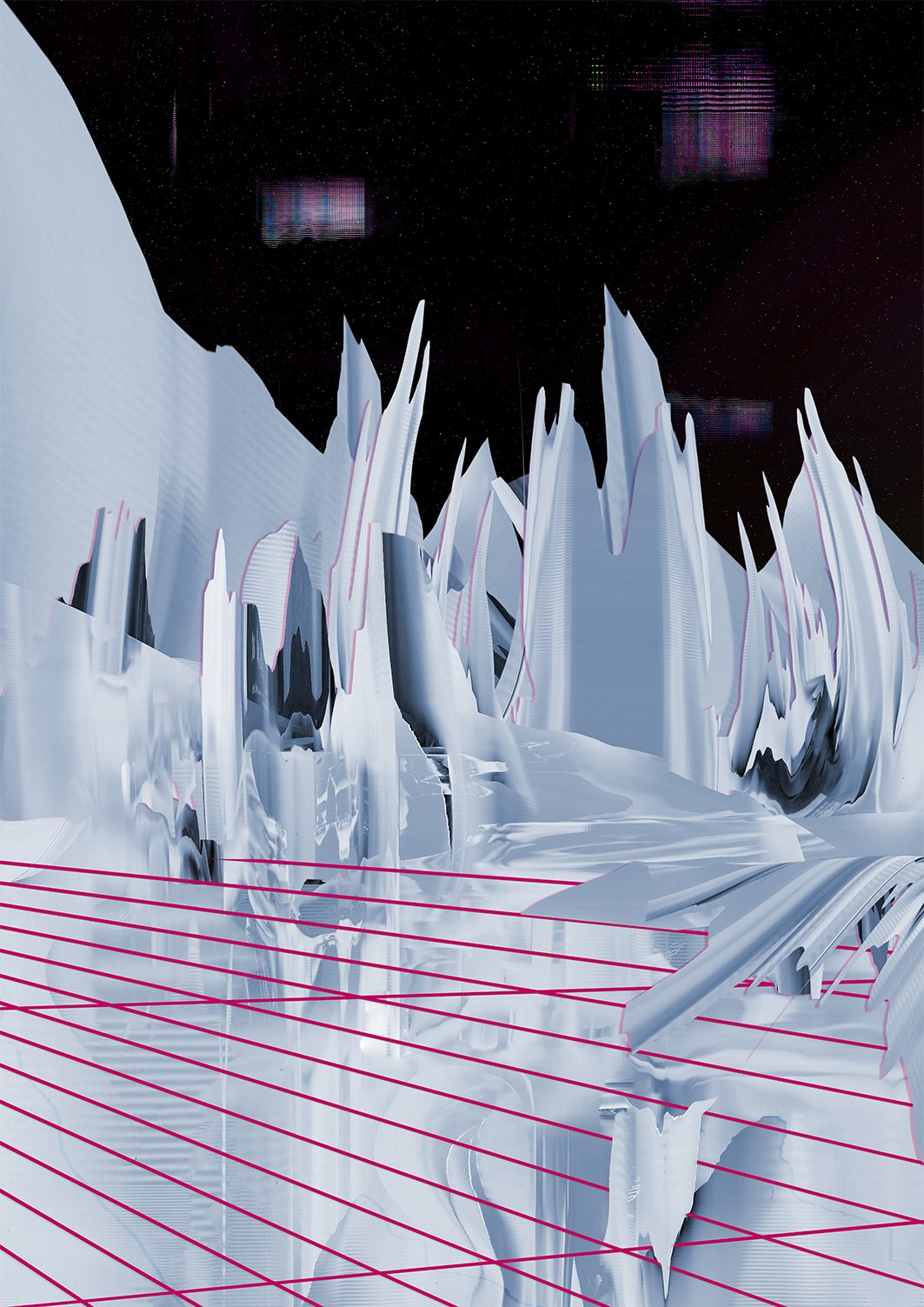

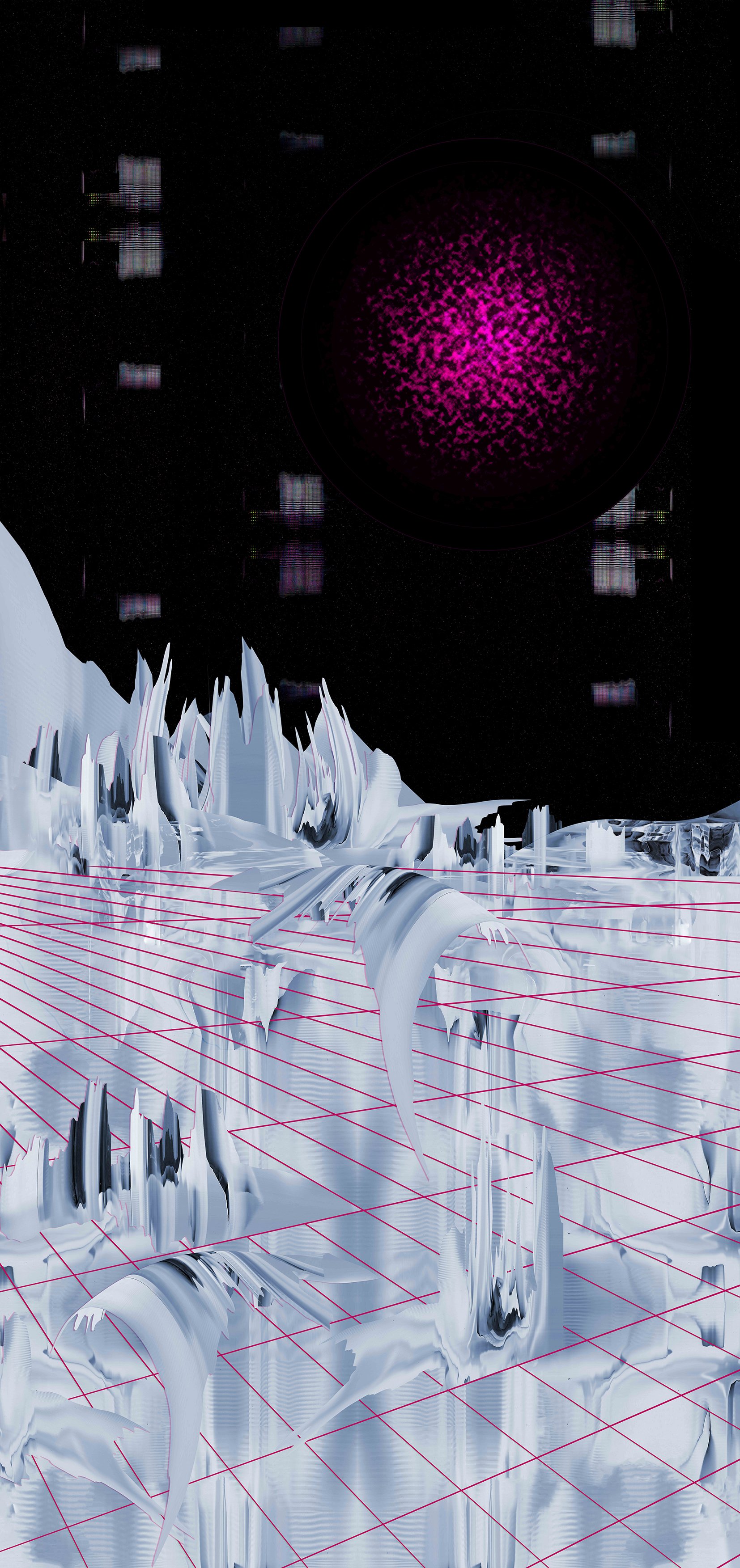

‘A Garden to Banish Loneliness’ was a multi-disciplinary installation shown at Studio 445 Window Gallery. The work continued the collective’s interest in collage and ephemera by reframing discarded or found materials into new speculative narratives.

Drawing inspiration from science fiction landscapes and depictions of garden environments in fairytales, the character of the installation changed as natural daylight gave way to the shimmers of grow lights; what appeared known or familiar during the day grew stranger and more alien as the light changed. The work built on recent projects that use climate change as a catalyst to reexamine our relationships with the environment, building continuities between historical records and hypothetical futures.

- interview with the artists about the work on 95bFM - Various Artists -

Found ephemera was collected from the area behind our home studio Daphne.

A note on science fiction

Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 science fiction classic ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ is one of the most analysed and reinterpreted films ever made. Its abstract and for many, bewildering, ending sequence has divided opinion since its release, with all manner of speculation attached to the iconic image of the ‘Starchild’ and the fate of protagonist David Bowman. Additionally, the film’s famous plot concerning the potent power of A.I. feels more relevant than ever as these previously speculative technologies increasingly become reality. There is another facet of the film however, which is less discussed but perhaps more revealing of the period in which it was made - its underlying optimism. Like many science fiction films of the 1960s, 70s and 80s, the future of humanity is one shaped by massive technological advancement, often coupled (as in 2001) with the greater exploration of space and the known cosmos. As the iconic sci fi films have aged, we have begun to reach the futures depicted in these films, finding them very different to what was suggested. From the 2019 of ‘Blade Runner’ (1982) to the 2015 of ‘Back to the Future II’ (1989), and certainly the 2001 of Kubrick’s masterpiece, the present looks nothing like what was imagined. Whether dystopian future-noir or family-friendly comedy, we have not kept up with our ambitious ideas concerning the pace of development.

*

If we briefly compare these classic films to more contemporary science fiction, a different trend is apparent. A quick scan of more recent titles like ‘Annihilation’ (2018), ‘Extinction’ (2018), and ‘Oblivion’ (2013) already speaks to the increasing pessimism of our creative epoch. Likewise, some of the biggest television franchises of recent years such as ‘The Walking Dead’ (beginning 2010) and ‘The Last of Us’ (2023, though based on the 2013 video game) show a society splintered to the point where violence between survivors is often presented as the greatest challenge they face. These post-pandemic/sickness/disease themed stories have taken on a frightening prescience in the post-Covid era, particularly with regard to the fracturing of our political conscience and in some cases, the wholesale rejection of science. Where once the future was characterised by technological development, now we see one defined by environmental collapse and/or A.I. induced destruction. Where once we saw the expansion of collective knowledge and understanding as our defining achievement, we now see it as the purview of an ‘elitest’ enemy, a “progressive” (framed entirely as a pejorative) force to be fought and campaigned against.

*

Science fiction has also frequently framed the greater exploration, and to some extent colonisation of space, as intrinsic to the future of mankind. One the genre’s grimmest and most horrifying franchises, which began with the film ‘Alien’ (1979), starts with a commercial space tug stopping on a small moon during a return run to Earth, suggesting the growth of capitalism into deep space. ‘Total Recall’ (1990) takes place on a colonised Mars, while ‘Blade Runner’ (1982) frequently references the opportunities to be found via the ‘off-world colonies.’ In these films, civilisation, enterprise, politics - as we might understand them - all have a future beyond the confines of Earth. Many science fiction classics like ‘The Fifth Element’ (1997) also include prominent product placement even far into the future (in this case, the year 2263), suggesting that major corporations and brands like McDonalds and Sony are almost the only constants even as the environment and almost every other factor of life on Earth shifts and changes. Though no doubt depicted at least partially tongue in cheek, this nevertheless speaks to a certain sense of inevitability about the future of the economy.

*

In 2023 however, the idea of space exploration/colonisation progressively feels less like the addition of territory to the world(s) we know and populate and more like a desperate search for an alternative - a quest for a ‘planet B.’ The ‘planned obsolescence’ of the contemporary free market now seems to increasingly be understood in relation to our environment; that the future of space exploration is defined by the activities of people like Elon Musk, Richard Branson and Jeff Bezos should give us all pause. True to form, this anxiety also plays out in more recent science fiction films. The later chapters of the ‘Alien’ franchise like ‘Prometheus’ (2012) and ‘Alien: Covenant’ (2017) for example, concern billionaire Peter Weyland’s personal pursuit of immortality which retroactively causes the events of the whole franchise, aided by an evil A.I. with his very own god-complex. Our speculative futures are being swallowed by our contemporary angst.

*

At almost every turn, it appears we are hurtling towards a future best defined by Fredric Jameson and Slavoj Žižek where it is indeed “easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.” Is another future no longer possible?

*